Advice for the Long Descent

I've listened to The Great Simplification (GS) podcast by Nate Hagens for more than one year now since it started and still find it educational and provocative. Kudos, Nate!

At the end of most episodes, Nate asks his guests what advice they have for young people seeking constructive action in the face of our global crises of climate, energy, minerals, topsoil, and so on. That's a great question, and i'd like to answer it myself here to clarify my thinking on the matter. What would i say to youth?

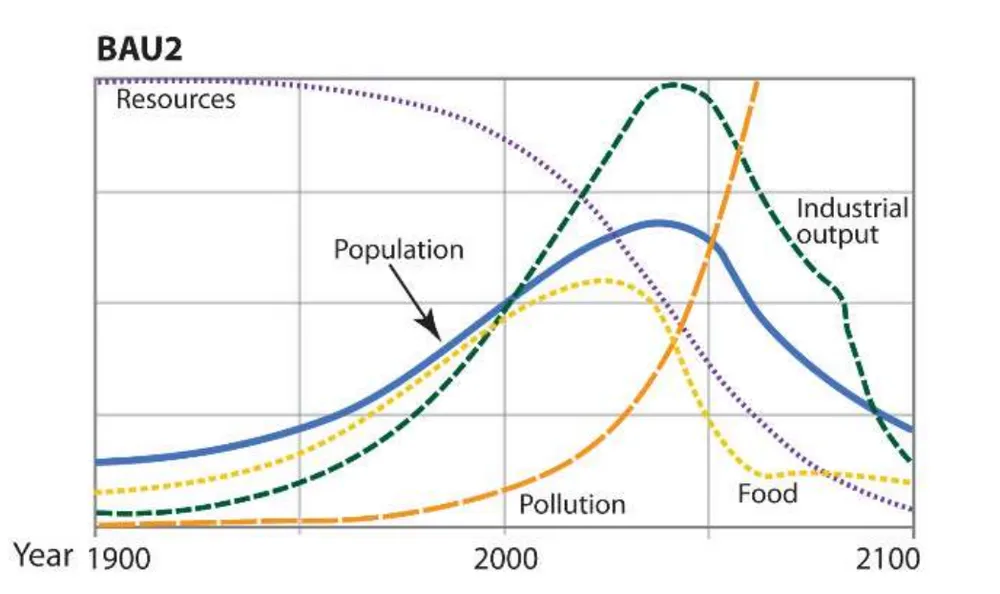

According to the Global Footprint Network, humanity entered ecological overshoot, a potentially terminal condition, around 1972. If we continue to pursue business as usual, human population and world industrial production will peak around 2040, then decline precipitously, according to the best-tracking and most realistic scenario (BAU2 pictured above) of the the latest World3 model. Coincidentally, the findings of the first version of the World3 model were published in 1972, our first year of overshoot. We've ignored these and related scientific warnings for over 50 years now, and at this late stage, i don't think we can avoid the fall of industrial civilization. But at least we can slow the descent. (A collapse in human population, by the way, is a good thing from the point of view of every other species on Earth.)

To that end, i offer the following three chunks of advice, mustered from my GS-related learnings. The advice is specific enough to act upon and benefit from quickly but also general enough to suit a variety of temperaments, locales, and scales of action. I hope it helps. For complementary advice and broader context, i highly recommend John Michael Greer's book The Long Descent.

"The shortsighted choices and missed opportunities of the last thirty years have given us a future in which energy will become drastically more expensive when it can be obtained at all. At this point in history, this unwelcome transformation can’t be prevented. Today’s national and regional governments are so blinkered by the myth of progress and so beholden to the existing economic order that the chance they’ll pursue a constructive response to our predicament at this point is minimal at best. The one remaining option is preparation on the personal, family, and community level." ~John Michael Greer, The Long Descent, 2008

- Learn about the root cause of our global crises. This will help you respond appropriately. The root cause is human overshoot enabled by fossil fuel use. For more details, see GS episode 53 with William E. Rees and the Global Footprint Network website, for example. Study this material and talk it over with your family and friends.

- Build resilience to withstand the shocks ahead as overshoot degrades our current life support systems.

Start with your person and household, because you can change those immediately, then work in widening social circles.

Do not rely on government (non-)action.

- Migrate, if you are willing and able, to a place with good climate, ecological, and social prospects. For example, if you live in Indonesia, you might move polewards to New Zealand to escape extreme wetbulb temperatures, ecological debt, and a fragile government.

- Collapse now and avoid the rush. That is, simplify your lifestyle to consume less energy, stuff, and stimulation (LESS), before you are forced to as global net energy declines. This will afford you material, temporal, and psychological slack. You will also discover that it's perfectly possible to live a happy and healthy life on less than a quarter of the energy used by an average American. For example, you might lower your living expenses to spend less time in paid employment and more time in meaningful work. The two often differ.

- With your new slack, study permaculture, a set of ethics and design principles for sustainable living. This will help you think in systems and learn practical skills. See David Holmgren's book Retrosuburbia and Andrew Millison's YouTube channel. For example, you might grow your own vegetables and give the surplus to your neighbors, thereby eating healthier, becoming more self-reliant, and getting to know your neighbors, with whom you'll need to cooperate.

- Shift some of your effort from the monetary economy to the core economy (of gift, barter, time banking, etc.). This will stregthen your social ties and reduce your exposure to our fragile financial system, which Nate reckons will take a major hit by 2030. For example, you might share tools with your neighbors, so that you don't all buy sledgehammers. Similarly, eliminate and avoid big financial debt (of more than one month's wages, say), because it's crippling to service during economic storms. Also keep in mind that financial capital is just one of many forms of wealth.

- Take charge of your own healthcare. As cheap, abundant energy disappears, so will energy-intensive, international-supply-chain-dependent medical treatments. So learn to maintain your health and treat minor ailments and accidents. For example, you might get and study the classic and perhaps most widely-used health care manual in the world, Where There Is No Doctor. Here's a PDF of the 2011 edition.

- Cultivate psychological resilience to cope, thrive, and inspire others in the tumultuous times ahead. There are many ways to this, as mentioned in that Wikipedia link. Start with one that appeals to you. For example, you might work on the American Psychological Association's top ten list. You might also read world history and ecology to reframe our current crisis in a broader context. Like ecosystems, complex societies give way to smaller and simpler ones as their maintenance costs exceed their resource base. This is the way of the world and not its end.

- Strengthen and expand your social network. Because the basic unit of human survival is the community, not the individual. For example, you might start a neighborhood food co-op where you organize periodic, big, discounted purchases of local food.

- Pass on a valuable low-tech skill to future generations. They will need all the help they can get. For example, teach others how to make rocket stoves or how to resolve conflict and encourage them to do the same. These skills will probably be useful for thousands of years, whereas programming computers, or any other skill whose technological suite depends on cheap, abundant energy and high-grade minerals, both of which are fast fading, probably won't.